Electrical engineering

Accessories and equipment for transformers. What's worth having on hand?

Anyone who has worked with transformers for more than one season knows this scenario.

The documentation checks out, the parameters are calculated, the handover passed without remarks.

The transformer is in place. It's operating. And for a long time, nothing happens.

Then one day, an alarm sounds, there's a smell of heated oil, or irritating vibrations spread through the entire station. That's when the sentence we all know is uttered:

But everything was brand new! 🤬

The problem is that a transformer is never a solitary device.

It's the center of a small ecosystem. Current, heat, vibrations, moisture, dust, mechanical stresses. They all circulate around it daily. Accessories aren't just aesthetic or catalog add-ons.

They are the tools that allow this ecosystem to remain stable.

This article is a map for thinking about which transformer accessories are worth considering from the start, because later they become the answer to questions that arise under stress, often after the fact.

Reading time: ~10 min

Why transformer accessories determine trouble-free operation

A transformer ages slowly and very consistently.

Insulation loses its properties with temperature.

Oil degrades faster if it's not monitored.

Mechanical vibrations, even minor ones, can over years cause more damage than a single overload.

These are processes you can't see at first glance.

That's why experienced operators say plainly: a transformer without monitoring accessories is a device operating in the dark. And working in the dark always ends in reaction instead of prevention.

In the following chapters, we'll go through the most important groups of accessories.

From electrical components, through temperature measurement and monitoring, to mechanics and cooling.

Each one addresses real problems that genuinely occur.

Insulators and connections, or the first line of electrical peace

It always starts with the connection.

And that's not a coincidence or a figure of speech.

All the electrical systems in the world, regardless of voltage and power, boil down to one question:

how to safely and stably transfer energy from one element to another?

Cable, busbar, transformer termination.

It is precisely at this point that two orders, which by nature don't get along, meet.

The electrical order and the mechanical order.

On one hand, we have voltage, electric field, current, temperature.

On the other, mechanical forces, vibrations, thermal expansion, the weight of conductors, and movements resulting from the operation of the entire system.

The insulator is the element that must reconcile these worlds.

It must provide electrical insulation while simultaneously transferring mechanical loads.

It must maintain the geometry of the connection while preventing discharges.

It must be invisible in daily operation but absolutely reliable for years.

It is precisely at these connection points where problems most often begin, remaining hidden for a long time.

Local overheating due to insufficient contact pressure.

Surface micro-discharges that don't yet trigger protection but already degrade the insulation.

Slight loosening of connections caused by heating and cooling cycles.

The transformer as a whole may appear healthy, while its weakest points are operating at the edge of tolerance.

In the case of medium-voltage cable terminations, the method of securing the conductor is fundamental. A cable is not a static element. It changes its length with temperature, transmits vibrations, and is sometimes subjected to additional installation stresses. If the connection lacks controlled pressure, contact resistance appears.

And where there is resistance, heat appears.

In practice, the question often arises: what insulator to choose for a medium-voltage cable termination?

In such cases, medium-voltage cable terminal insulators are used, which provide a stable connection and controlled conductor pressure. Their task is not just electrical insulation.

They actively stabilize the connection.

They ensure uniform and repeatable conductor pressure, regardless of whether the installation is operating in winter at low temperatures or in summer under full load.

This solution is particularly important in stations where cables are long, heavy, or routed in a way that generates additional mechanical forces.

A well-chosen insulator with a terminal ensures the connection maintains its parameters not just on the day of handover, but also after 5 or 10 years of operation.

In installations based on busbars, the problem looks somewhat different.

A busbar is rigid, massive, and transmits much greater forces.

There is no room for random tolerances here.

Precision in positioning and resistance to vibrations resulting from high current flow and electrodynamic phenomena are what count.

Insulators with busbar clamps serve as precise support and guide points.

They maintain a constant system geometry, prevent busbars from shifting, and protect connections from loosening. Thanks to them, contact parameters remain stable even during prolonged operation under high load. This is especially important in industrial installations where a transformer doesn't operate occasionally, but daily, often close to its design limits.

Oil-air bushings are a separate category.

They are responsible for one of the most difficult tasks in the entire transformer.

Safely transitioning voltage from the oil-filled interior to the outside, to the air environment. In this single element, different dielectrics, different tempreatures, and different environmental conditions meet.

An oil-air bushing must be sealed, resistant to aging, contamination, and moisture.

Any weakening of its properties can lead to surface discharges, and in extreme cases, to a loss of the transformer's seal. Silicone versions are increasingly chosen today because silicone handles contamination, rain, UV radiation, and variable weather conditions excellently. Even when the insulator's surface isn't perfectly clean, silicone retains its dielectric properties.

This is precisely why silicone oil-air bushings have become the standard in modern transformer stations. Not because they are trendy, but because they better withstand the real world.

And the real world, as we know, is rarely laboratory-clean ;-)

In environments requiring particular mechanical flexibility, EPDM (Elastimold) insulators are also used. EPDM is, in simple terms, a special type of technical rubber, designed to work where ordinary materials would quickly give up. It's not soft rubber like in a tire nor brittle like plastic. It's an elastomer, i.e., an elastic material that, after deformation, returns to its shape and doesn't lose its properties for years.

You could compare it to a very durable seal that doesn't harden in the frost, doesn't crack in the sun, and doesn't crumble over time. EPDM withstands continuous vibrations, temperature changes from frost to high heat, and the effects of moisture and ozone present in the air.

In practice, this means that components made of EPDM don't 'age nervously'.

They don't crack suddenly, don't lose elasticity, and don't require frequent replacement.

Therefore in compact transformer stations and prefabricated solutions, where everything works close together and is subject to constant micro-movements, EPDM performs significantly better than rigid insulating materials.

Tapered bushings, or safe passage through the housing

A tapered bushing is a component rarely talked about until it starts causing problems.

And it is precisely this component that is responsible for one of the most critical points in a transformer:

the passage of voltage through the housing.

Leaks, micro-cracks, improper installation.

Any of these factors can lead to moisture ingress into the insulation and, consequently, to accelerated transformer aging.

That's why tapered transformer bushings are no place for compromises.

A well-chosen bushing ensures electrical stability, oil tightness, and mechanical strength. In practice, its quality directly translates to the lifespan of the entire device.

In many cases, upgrading the bushing solves problems that were previously attributed to the windings or oil.

Oil and winding temperature, or what really ages a transformer

If there is one parameter that most affects a transformer's lifespan, it's temperature.

A transformer doesn't wear out because it's old.

It wears out because it's too hot.

Sometimes just a little too hot, but for long enough.

In the physics of electrical insulation, there is no mercy or romanticism. There is temperature and time. The rest are consequences.

For decades, it has been known that every increase in winding temperature above the design value dramatically accelerates insulation aging. Every 6 to 8 °C above the nominal operating temperature can halve the insulation's lifespan.

This isn't a textbook curiosity; it's hard operational reality.

For a transformer, this means a reduction in life not by a few percent, but by half.

And most interestingly, this process happens quietly. Without sparks, without noise, without an alarm at startup.

The oil in a transformer cannot be treated solely as an insulating medium.

It is primarily a carrier of information about the device's condition. Its temperature speaks volumes about what's happening inside, even when the windings are still invisible and inaccessible. Therefore, measuring the oil temperature is not an add-on or a premium option. It's an absolute minimum if we want to know how the transformer is really performing.

The simplest and still very effective form of control is transformer oil temperature indicators. Mechanical, without electronics, resistant to environmental conditions. Their huge advantage is immediacy.

A single glance is enough to know whether the device is operating within a safe range or is starting to approach limits that are better not exceeded too often.

When the installation becomes more demanding and loads variable, information alone is no longer enough. This is where temperature controllers, such as the CCT 440, working with PT100 sensors, come into play. This is no longer just measurement. This is temperature management.

Automatic cooling activation, alarm signals, the possibility of integration with a superior system. The transformer stops being mute and starts actively communicating its state.

PT100 sensors for transformers have become standard for a reason.

They are stable, precise, and predictable.

They can be used for both oil temperature measurement and direct winding measurement.

It is precisely they that provide the data which allows for a reaction earlier, before elevated temperature turns into a real operational problem.

DGPT2 Monitoring and RIS Systems - or when a transformer starts to speak

A transformer communicates with its surroundings constantly.

It never operates in silence. It is always signaling something.

It changes oil temperature, reacts with increased pressure inside the tank, generates gases resulting from insulation aging or local overloads.

These phenomena occur regardless of whether anyone is observing them.

The problem is that without appropriate sensors, these signals remain unnoticed.

For the transformer, this is its natural language. For a person without monitoring, it's just background noise.

And it is precisely in this space between phenomenon and information where failures occur, later labeled as 'sudden'.

The DGPT2 system is a classic protective and measuring device used in oil-immersed transformers.

It monitors three basic parameters: Gas, Pressure, and Temperature.

The presence of gas signals processes occurring in the oil and insulation.

A rise in pressure informs about dynamic changes inside the tank.

Temperature allows for assessing the transformer's thermal load.

DGPT2 operates locally and provides clear alarm signals or triggers protective actions.

The RIS system, on the other hand, is a strictly monitoring solution focused on observing trends and analyzing the transformer's condition over time.

It collects data, archives it, and enables interpretation without the need to shut down the device.

Thanks to this, an operator can see not only that a parameter was exceeded, but also how it happened. Whether the temperature rose gradually or suddenly. Whether pressure changes are one-off or repetitive.

Not long ago, both DGPT2 and RIS systems were mainly associated with large transmission stations. Today, they are increasingly used in medium-sized industrial installations and renewable energy farms.

The reason is simple and very pragmatic.

Installation downtime costs more than a monitoring system.

Thanks to such solutions, the operator doesn't learn about a problem at the moment of failure or protective device operation.

They learn earlier, when they still have time to make a decision.

They can schedule maintenance, adjust the load, or check cooling conditions.

The transformer ceases to be a black box and starts being a device that speaks before it starts screaming.

Vibrations and mechanics, the signs of a transformer's life

A transformer vibrates.

Always.

Even a brand new one, fresh after handover, that still smells of paint.

This is not a factory defect or a sign of problems.

The magnetic field, electrodynamic forces, and the core's operation cause the device to live by its own, very subtle rhythm. This isn't visible in catalog data, but it's audible and tangible in the real world.

The trouble begins when these natural vibrations don't stay where they should.

Instead of dissipating within the transformer's structure, they travel further.

To the foundation, to the station housing, to building walls, and sometimes even to neighboring equipment. Then a faint humming appears, followed by irritating noise, and after years, minor cracks, loosened bolts, and components that have... simply shifted apart.

Vibration damping pads for transformers are one of those accessories that rarely impress at the project stage but earn huge points during operation.

They act like shock absorbers. They isolate vibrations from the rest of the structure, reduce noise, and ensure the foundation doesn't have to participate in every impulse of the transformer's work.

It's a simple, somewhat underappreciated, and very effective solution.

In many facilities, it's precisely the lack of vibroacoustic separation that turns out, after years, to be the cause of mechanical problems described with one word: wear and tear.

And the truth is often more prosaic. The transformer was simply gently reminding everyone of its existence the whole time, and no one gave it pads so it could do so more quietly.

Ventilation and cooling, or when nameplate power meets summer

Every transformer has its proud rated power listed in the documentation.

The numbers match, the calculations too. The problem is that these values are very often derived under conditions with only moderate connection to reality. A friendly ambient temperature. Proper ventilation. No heatwaves, no dust, no enclosed station standing in full sun.

And then summer comes.

Concrete heats up like a frying pan. The air in the station stands still.

The transformer does exactly what it always does: dissipates heat.

Only suddenly, it doesn't really have anywhere to put it.

And here begins the real verification of nameplate power.

Transformer overheating rarely starts dramatically.

First, there are a few extra degrees on the oil. Then more frequent fan operation, if there are any at all. Sometimes the need arises to limit load during peak hours.

Seemingly nothing serious, but each such episode adds its brick to the accelerated aging of the insulation.

AF fans for transformer cooling are the answer precisely for this moment when theory meets climate. Their task is simple and very specific. To increase heat exchange where natural convection is no longer sufficient.

Without interfering with the transformer's construction, without replacing it, without a revolution in the design.

That's why AF fans are used both in new installations, as a planned element from the start, and in the modernization of existing stations.

They often appear where a transformer is technically sound, but its operating conditions have changed over time. Greater load. A different consumption profile. Higher ambient temperatures than a decade ago.

In practice, it's precisely additional cooling that very often solves a problem that previously seemed serious.

Instead of constantly balancing on the edge of its power rating, the transformer returns to calm operation.

Instead of plans for costly replacement, reasonable support for heat dissipation is enough.

Cooling doesn't magically increase a transformer's power.

It allows it to safely utilize what it already has.

And in operation, that can be the difference between comfort and constantly worrying if it's going to be too hot again today.

Accessories as a system, not an add-on

The biggest mistake in approaching transformer accessories is treating them like a list of options to tick off at the end of a project. One here, another there, just to have them.

Meanwhile, in real operation, they don't work separately.

They cooperate. They form a system of safety, control, and daily operational comfort.

Insulators ensure energy has a stable path.

Bushings guard the boundary between the interior and the external world.

Sensors and monitoring provide information before a problem appears.

Vibration pads and fans take care of mechanics and temperature, things that work continuously, even when no one is looking.

Each of these elements addresses a very specific situation that, in practice, happens more often than we'd like.

A transformer equipped with such accessories isn't more complicated.

It's simply more resilient to reality. To summer, to variable loads, to vibrations, to time. And time, as we know, is the most demanding test for any installation.

If you've made it to this point, it means you think about transformers not as catalog objects, but as systems that need to work for years.

At Energeks, we believe in a partnership approach. We don't look at a transformer as a single device taken out of context, but as an element of a larger system that must operate stably for years. That's why, when designing and selecting transformers, we always consider the operating conditions, future load, and the realities of operation.

If you want to see which transformers and system solutions best fit your installation, we invite you to explore the Energeks offer.

And if you'd like to stay longer, exchange knowledge, and see what the world of transformers really looks like behind the scenes, join us on LinkedIn.

This blog is an invitation to systems thinking. And to further conversations.

Sources:

IEC 60076-1: Power Transformers - General Standard via studylib.net

Winter is when everything comes to light.

For most of the year, the installation works correctly.

The oil transformer has a power reserve. Voltage stays within limits. There are no complaints, no alarms, no phone calls from users.

And then the first cold wave hits, and suddenly something no one planned for begins to happen.

Flickering lights. Notifications about voltage being too low.

Heat pumps that shut down exactly when they are needed most.

In the background, a transformer that according to the documentation "should handle this," but in reality is operating on the edge of stability.

This isn't a story about faulty technology.

It's also not a tale of user errors.

It's a story about the collision between a new way of using energy and infrastructure that was designed under completely different circumstances.

Heat pumps have changed the network load profile.

They did it quickly, massively, and often without a parallel shift in thinking about medium voltage transformers. The annual energy consumption still adds up. The nameplate power looks reasonable.

And yet, in winter, voltage drops, alarms, and questions arise that are difficult to answer in a single sentence.

Why do problems start precisely when the temperature drops below zero?

Why does an oil transformer, which operates calmly in summer, react completely differently in winter?

And why does the classical approach to power rating selection stop being sufficient in a world of mass-scale heat pumps?

This article was created to organize these phenomena.

Without scaremongering about failures. Without oversimplifying the physics. Without shifting blame to one side.

We will show what the load generated by heat pumps really looks like during the heating season, how an oil transformer reacts to it, where voltage drops occur, and why they are not random.

And what can be done before the only answer becomes a costly modernization.

If you are responsible for the network, a project, a facility, or investment decisions, this text will help you look at the problem from a broader perspective. One that considers both the technology and the real operating conditions.

Reading time: approximately 13 minutes

How heat pumps really stress the grid in winter

In summer, a heat pump is almost invisible to the grid.

It operates sporadically, mainly for domestic hot water. Its momentary power draw is moderate, and its load profile blends into the background of other consumers. An oil transformer sees it as just one element among many in the landscape.

In winter, the situation changes radically.

The heat pump stops being an add-on. It becomes the primary source of thermal energy, and therefore a device operating for long periods, intensively, and often in sync with hundreds of other similar installations on the same network.

One key word here is: momentary power.

Project documents most often analyze annual consumption. The kilowatt-hours add up, the SCOP coefficients look good, and the energy balance seems reasonable. The problem is that a transformer doesn't see kilowatt-hours. It sees amperes, here and now.

And in winter, "here and now" looks different than in summer.

When the temperature drops below zero, the demand for heat increases. The heat pump's compressor runs longer and more frequently. Its momentary efficiency drops, so generating the same amount of thermal energy requires more electrical energy. Add to this the defrost cycles of the evaporator, which generate short-term but repetitive power draw spikes.

On the scale of a single house, this still looks innocent.

On the scale of a housing estate, a facility, or an area supplied by one MV/LV transformer, the cumulative effect begins.

Everyone heats at the same time.

The coldest days mean peak load occurs at exactly the same morning and evening hours. The grid has no time to "breathe," and the transformer enters prolonged operation near the limits of its thermal and voltage capabilities.

This is where the first paradox appears, which often surprises investors and designers.

An oil transformer may not be overloaded in terms of power, yet it can still cause problems.

Why?

Because the problem isn't always exceeding the nameplate rating. Often, it is the voltage drop resulting from the nature of the load.

Heat pumps, especially inverter-driven ones, are not linear loads. Their current draw changes dynamically. At low temperatures, the current on the low-voltage side increases, and every additional ampere means a greater voltage drop across the transformer's impedance and the supply line.

In summer, the same transformer operates at a higher secondary voltage, lower current, and with a large regulatory margin. In winter, that margin disappears.

If we add to this networks designed decades ago with the assumption that the main loads would be lighting, appliances, and occasional electric heating, the picture becomes clear.

This isn't a failure.

This is a change in boundary conditions that the infrastructure simply wasn't designed for.

In the next part, we'll take a closer look at how an oil transformer reacts to such a load from a physics perspective. Without myths about "overheating in winter" and without magical explanations. Only what really happens in the core, windings, and oil when the grid starts breathing frost.

What really happens inside an oil transformer during a frost

From the outside, a transformer looks the same in July and January.

The same enclosure. The same oil. The same parameters on the nameplate.

The difference begins on the inside.

An oil transformer does not react to winter in an intuitive way. The low ambient temperature is not a problem in and of itself. Quite the contrary. Cooling is more efficient then. The oil dissipates heat to the surroundings more easily, and the thermal headroom seems larger than in summer.

And it's right here that a false sense of security is born.

Because in winter, the problem is not the transformer's temperature. The problem is voltage and current.

When the load on the low-voltage side increases, the current in the windings rises. Along with it, copper losses—proportional to the square of the current—increase. This phenomenon is well known and accounted for in design.

But simultaneously, the voltage drop across the transformer's impedance increases.

Every transformer has its short-circuit impedance. This is not a flaw or a random feature. It is a design parameter that determines how the transformer will behave under load and during a short-circuit.

The greater the current, the greater the voltage drop.

In summer, this drop is hardly noticeable. In winter, under prolonged load close to peak, it begins to be felt by the connected equipment.

Heat pumps are particularly sensitive to this.

The inverters controlling the compressors have their own lower voltage thresholds. When the voltage drops too low, the electronics react immediately. First, it limits power. Then it goes into an alarm state. Finally, it shuts the device down.

From the user's perspective, this looks like a random failure.

From the transformer's perspective, it's a logical consequence of operating under conditions the network wasn't designed for.

A further domino effect occurs.

When some heat pumps shut down due to low voltage, the load temporarily decreases. The voltage bounces back up. The devices attempt to restart. The inrush current appears simultaneously at many points in the network.

The transformer receives a series of load impulses that further destabilize the voltage.

This is not an overload in the classical sense.

It is an operational instability resulting from the nature of the loads and their synchronization.

This often leads to a question about the transformer's tap changer.

If the voltage is dropping, maybe it's enough to raise it.

Sometimes this helps. Sometimes it just shifts the problem elsewhere.

Raising the secondary voltage increases the margin for heat pumps, but it also raises the voltage during hours of lighter load. This can lead to exceeding permissible voltage levels for other consumers. Especially where the network is short and has low impedance ("stiff").

A transformer does not operate in a vacuum. It is a part of a system.

If the system has changed, the transformer begins to reveal its weak points.

In the next part, we will examine why classical methods for selecting transformer power ratings are becoming insufficient in a world of mass-scale heat pumps and what warning signs appear long before the first winter alarm.

Why the classical power rating selection method stops working

For years, everything was logical and predictable.

Selecting a transformer was based on installed power, simultaneity factors, and annual energy consumption. Add a small safety margin—sometimes 10 percent, sometimes 20. In most cases, that was enough.

Because the loads were passive and spread out over time.

Lighting, motors, household appliances. Each had its own operating rhythm. Even if several devices turned on at the same time, the scale of the phenomenon was limited.

Heat pumps have changed this order.

Not because they are faulty. Not because they draw "too much current." They changed it because they introduce a strong temporal correlation of load.

When it gets cold, they all want to run. At the same moment. For many hours without a break.

Classical simultaneity factors begin to lie. On paper, everything adds up. In reality, the network sees nearly the full load for a long time, not short inrush peaks.

Another element, often overlooked in analyses, comes into play.

A transformer is selected based on active power. Winter problems very often start with reactive power and the nature of the current.

The inverters in heat pumps improve the power factor (cos φ), but they don't completely eliminate current distortions. Harmonics, especially lower-order ones, increase the effective current without a proportional increase in active power. The transformer sees a greater current load, even though the energy meter doesn't show it directly.

This is another reason why "the kW adds up," but the voltage drops.

In practice, this means a transformer selected perfectly according to the old methodology can operate in winter under conditions no one considered. Not as a short-term exception, but as a new norm.

The first warning signs appear early.

They are not failures or protection tripping.

They are subtle symptoms that are easy to ignore.

Voltage at the lower limit of the norm in the morning hours. An increased number of voltage alarms in the inverters. User complaints that "something sometimes flickers." Logs from monitoring systems showing long periods of high load without distinct peaks.

This is the moment when the network is still working. But it has no margin left.

Many investment decisions are made only after the first serious problem appears. In winter, under time pressure, user dissatisfaction, and weather conditions. This is the worst possible moment for a calm analysis.

That's why, in the next part, we will move on to what can be done earlier.

What diagnostic tools truly provide answers, how to distinguish a power problem from a voltage problem, and when a transformer is actually undersized, versus when it's simply poorly matched to a changed network.

What to check before a real problem begins

In winter, the network doesn't forgive illusions.

If the first signs of instability appear, it means physics has already sent a warning signal. It's just not screaming yet.

The most common mistake is trying to answer with a single parameter. Transformer power rating. Cable cross-section. Protection setting. However, winter problems rarely have a single cause.

It starts with measurements. But not the kind that last a few hours on a random day.

A seasonal picture is needed.

Load profiles from summer and winter periods. At least several weeks of data. Preferably with fifteen-minute or shorter resolution. Only then can you see whether the load is impulsive or continuous. Whether the voltage drops slowly or collapses sharply at specific times.

A transformer rarely lies. It simply shows what the network is doing to it.

The next step is to analyze voltage at several points in the low-voltage network, not just at the transformer terminals. The voltage drop at the transformer might look acceptable, while at the end of a supply line it exceeds permissible limits.

This is especially important where heat pumps have been added to existing buildings without upgrading lines and distribution boards.

It's also worth looking at what happens with reactive power and effective current.

If the current rises faster than the active power, it's a signal that the transformer is being loaded in a way that isn't visible in standard energy consumption summaries. Harmonics, phase imbalance, and uneven switching of loads can eat up the margin faster than you think.

A frequently overlooked element is voltage regulation.

Transformer tap settings are often based on historical conditions, from before the facility's modernization. Changing one tap step can improve the situation in winter, but only if preceded by an analysis of voltages across the entire load range. Otherwise, the problem will shift to summer.

This brings us to an important distinction.

Not every winter problem means the transformer is too small.

Sometimes its power rating is sufficient, but it's operating in a network with too high impedance. Sometimes it's correctly sized, but the load is too strongly time-correlated. And sometimes the limit has indeed been exceeded, but no one wanted to call it by its name earlier.

A good diagnosis allows you to choose the right tool.

Upgrading the transformer is one of them. But it's not always the first, nor the most sensible, option.

We've covered this topic in more detail in a separate article:

Renovate or replace? The last chance for your transformer!

In the next part, we'll show which action scenarios are realistic in practice. From the simplest operational adjustments, through changes in network configuration, to investment decisions that only make sense when they are based on data, not winter panic.

How to design and operate transformers in a world of heat pumps

The biggest change in recent years hasn't been about the transformers themselves.

It's about the way we think about the network.

For decades, design was an attempt to predict averages. Average consumption. Average peaks. Average customer behavior. This model worked as long as appliances had different rhythms and didn't respond en masse to the same stimulus.

Heat pumps respond to temperature. Simultaneously. Without negotiation.

This means the network must be designed for extreme scenarios, not just for the annual balance.

A transformer ceases to be merely a source of power. It becomes an element of voltage stabilization under conditions of prolonged load. This changes the selection criteria.

Increasing importance is placed not only on the nameplate rating, but on the transformer's impedance, its voltage regulation characteristics, and its cooperation with the rest of the infrastructure. Two transformers with the same power rating can behave completely differently in winter if they have different short-circuit impedances or different regulation capabilities.

Operation also requires a new approach.

Instead of reacting to failures, it's worth observing trends. Are minimum voltages dropping year by year? Is the operating time under high load lengthening? Is the number of power electronic loads growing faster than assumed?

These are signals that appear long before a crisis.

A well-designed network with oil transformers is not afraid of winter. It has a margin. It has flexibility. And above all, it has the awareness that the way energy is used has already changed and will not return to the state before mass-scale heat pumps.

Therefore, the key question today is not: will the transformer survive this winter?

The question is: will it still operate stably in five years within a network that is increasingly reactive to weather, automation, and simultaneity?

If the answer isn't clear, the best time to act is now. Calmly. With data. Without winter panic.

Because winter will always come. And the network should be ready for it before it gets truly cold.

In the end, it's worth putting a period in a place that doesn't close the topic, but opens up possibilities.

Today, the oil transformer is no longer a passive piece of infrastructure.

In the reality of mass-scale heat pumps, it becomes a tool for conscious management of voltage, losses, and network stability. A well-chosen, properly configured unit that meets current Ecodesign Tier 2 requirements — like the MarkoEco2 from Energeks — can regain the margin that is most sorely missed in winter. Not through oversizing, but through better power quality, lower load losses, and a true match for modern operating profiles.

Our current transformer offering has been designed precisely for such scenarios, where the network must operate stably not only today but also in the heating seasons to come.

It includes both oil transformers, proven in demanding operating conditions and resilient to prolonged winter loads, and dry-type transformers, chosen where fire safety, environmental conditions, or indoor installation are of key importance.

In both cases, the starting point is the same. Voltage stability, low losses, compliance with current energy efficiency requirements, and a genuine fit for modern load profiles—where heat pumps are no longer the exception, but the norm.

Thank you for your time and attention. If you are interested in such analyses, real project experiences, and thoughtful conversations about how the energy sector is changing from within, we invite you to our community on LinkedIn.

Sources:

International Energy Agency (IEA)

https://www.iea.org/reports/the-future-of-heat-pumps

ENTSO E

https://www.entsoe.eu/publications/system-development-reports/

2025. The year theory stopped being enough

The year 2025 did not bring a single, great technological breakthrough.

No miracle material appeared. Physics didn't change. No new law of electrical engineering was discovered.

Instead, something much less spectacular but far more painful happened.

Reality started to test assumptions.

Those that had worked "well enough" for years suddenly stopped holding up.

Projects copied from previous years began to fall apart during the execution phase. Budgets that were supposed to balance on paper started to leak in areas previously considered safe. Schedules based on standard solutions had to be corrected mid-game.

And it quickly became apparent that the transformer was no longer just part of the background.

In 2025, the transformer became a topic of conversation on construction sites, in design offices, and at investors' tables. It appeared in questions about energy losses, compliance with Ecodesign Tier 2, real operating costs, dimensions, logistics, and acceptance procedures. Increasingly, not as an isolated problem, but as an element that could decide the success of an entire project.

This was the year theory was invited onto the construction site. And it didn't always come out unscathed.

This text is not a product summary. It is a summary of experiences.

It is an attempt to gather conclusions from a year that very effectively separated convenient assumptions from true ones. It is written with designers, contractors, and investors in mind who don't want to enter 2026 relying on memory or shortcuts. Only with greater peace of mind and better insight.

Because if 2025 taught the energy industry anything, it's that not everything that worked yesterday works just as well tomorrow.

We didn't ask which transformer is the best. We asked which one stopped being a problem.

We are not creating a ranking. We are not selling promises. We are looking at the tensions that emerged in 2025 between regulations, physics, and budgets. We examine where theory diverged from practice and what decisions began to win out in real projects.

This is a story about losses that suddenly started to matter.

About power that stopped being just a number in a table. About documentation that could either save or stall an investment. And about why, in 2026, the question is no longer "what is the most powerful," but "what provides predictability."

Reading time: ~11 minutes

Ecodesign Tier 2 Stopped Being Theory. It Became a Reality Filter

Just a few years ago, Ecodesign Tier 2 was mainly a future concept in the industry.

Something that would "come into effect," "be mandatory," "need to be considered." In 2025, this mindset stopped working.

Tier 2 ceased to be a clause in a directive. It became a very practical filter through which real projects either started to pass or began to fail.

On paper, everything looked simple.

Lower no-load losses, better efficiency, compliance with the regulation. In practice, 2025 showed that not every transformer that "almost meets" the requirements actually meets them in the context of a specific installation. Differences of a few watts in no-load losses, previously ignored, started to matter. Not because everyone suddenly fell in love with efficiency.

But because energy stopped being cheap background noise and became a real cost.

In many projects, Tier 2 exposed old design habits.

Selecting a transformer "by eye," based on previous projects, stopped being safe. Solutions that had passed acceptance for years without major questions began to raise doubts in 2025. Additional queries, clarifications, and corrections appeared. Sometimes at the design stage, sometimes during execution, which always hurts more.

The problem wasn't the regulation itself.

It was that Tier 2 forced a confrontation with the transformer's actual operating profile. No-load losses, previously treated as a "fixed and negligible" cost, began to be analyzed on a yearly scale, not just at the moment of acceptance. In installations where transformers operate at low load most of the time, it suddenly turned out that these very losses determined the economics of the solution.

2025 also showed that not every project is equally ready for Tier 2.

In new installations, it was easier to incorporate the requirements from the start. In modernizations and expansions, the situation was often more complicated. Space constraints, existing infrastructure, and previous design assumptions could clash with the new requirements in a very unpleasant way.

Added to this was the issue of availability.

Last year, the market felt very clearly that a Tier 2-compliant transformer is not always an "off-the-shelf" item. Lead times, logistics, and delivery planning began to have a real impact on investment schedules. Projects that didn't account for this in advance often had to make up for lost time in other areas or postpone deadlines.

Another interesting phenomenon was how the narrative around Tier 2 changed.

The question "do we have to?" disappeared, and the question "how to do it sensibly?" appeared. Conversations increasingly focused not just on meeting the standard, but on the consequences of choosing a specific solution.

How will it affect losses in the long term? What about servicing? And future load changes?

In this sense, Ecodesign Tier 2 did the industry a favor. It didn't simplify life.

But it forced thinking in holistic, not just formal, terms. And it quickly became clear that in 2026, Tier 2 will no longer be a topic for discussion. It will be the starting point.

We wrote about no-load losses in Tier 2 and their translation into specific financial figures here—it's worth familiarizing yourself with this knowledge:

No-load losses in Tier 2 transformers. How to calculate the real cost?

Nameplate Rating Versus Real-World Usage

If one assumption was tested with particular harshness in 2025, it was the belief that a transformer's nameplate rating tells you everything about it.

For years, it was treated as a safe anchor. There's the number. There's the margin. There's peace of mind. The problem is that reality very rarely operates according to the same chart.

In 2025, many projects painfully collided with the fact that a transformer doesn't operate in a vacuum. It operates over time. In daily cycles. With seasonal patterns. In an environment of loads that changed their character faster than most design assumptions.

The classic mistake looked innocent. "Let's take a larger transformer, it will be safer."

Or the opposite. "The load profile looks light, we can reduce the power." On paper, it all added up. In the spreadsheet too. On the construction site and in operation, problems began.

Oversizing in 2025 ceased to be neutral.

A transformer operating most of the time at a very low load generates no-load losses regardless of whether it's delivering power or not. With rising energy costs, this became noticeable not after a year, but after a few months. Investors, who not long ago would have waved it off, began asking questions. Where do these numbers come from? Why don't the bills look as projected?

On the other hand, problems with undersizing emerged.

Especially where the load profile was based on historical data that didn't account for changes on the consumer side. Heat pumps, electric vehicle chargers, inverters, irregular operating cycles. All this meant that momentary overloads, starting currents, and short-term power peaks began occurring more frequently than anticipated.

In 2025, many people truly saw, for the first time, the difference between the nameplate rating and the transformer's actual behavior over time. A transformer can have a power reserve, yet operate under conditions that cause excessive heating.

It can formally meet requirements, yet practically shorten its lifespan. It can "manage," but at the cost of losses and operational stress.

A common source of the problem was a simplified approach to the load profile.

The average power over a day or month says little about what happens at specific moments.

And it is precisely these moments that determine how the transformer behaves. Short but intense loads can do more damage than stable operation at a higher level.

The year 2025 also showed that the conversation about a transformer's power cannot end with the number in its name. Increasingly, questions about the nature of the loads, their variability over time, and plans for installation development came to the fore. Designers began returning to investors more often with questions previously deemed unnecessary.

What will the load look like in two years?

What will change after expansion?

Which scenarios are realistic, and which are only theoretical?

All of this meant that in 2025, selecting a transformer's power rating stopped being a "just-in-case" decision. It became a strategic decision. One that must consider not only what is today, but what is very likely tomorrow.

And that is precisely why, heading into 2026, fewer and fewer people ask which transformer has the highest power rating. More and more ask which one best fits the actual way it will be used.

And that is a change that makes a huge difference.

Energy losses stopped being abstract. They started to cost, truly

For many years, transformer losses were one of those topics everyone was aware of, but few truly calculated. Sure, they appeared in documentation. Sure, they were listed in catalog sheets. But in practice, they were treated as a background cost. Something that "just exists" and doesn't require deeper attention.

The year 2025 ended this comfortable stage.

At the moment when energy prices stopped being a stable reference point and began to fluctuate in reality, transformer no-load losses stepped out of the shadows.

And they did so in a very unpleasant way. It suddenly turned out that differences which previously seemed cosmetic began to be noticeable in the operational budget over the course of a year.

The biggest surprise for many investors wasn't the load losses. Those are intuitively associated with the device's work. The real discovery turned out to be the no-load losses. Constant. Independent of the load. Present always, even when the transformer is mostly just "waiting."

In installations with uneven or seasonal operating profiles, it was precisely these losses that began to play the leading role. A transformer that was formally well-matched spent a large part of the year operating far from its optimal point. And energy was leaking away. Day after day. Without noise. Without alarms. Without visible symptoms, except for one thing that cannot be ignored: the bill.

2025 was also the moment when more and more projects began to be analyzed in terms of Total Cost of Ownership (TCO), not just the purchase price. TCO stopped being a trendy acronym. It became a defensive tool. Investors began asking not what a given transformer would cost at the moment of acceptance, but after five, ten, fifteen years of operation.

This changed the dynamic of conversations.

Cheaper solutions began to lose in the long-term horizon. A difference of a few percent in efficiency, previously considered a detail, in the new calculations could determine the profitability of the entire investment. And interestingly, these conversations increasingly took place not at the tender stage, but after the first year of operation, when the data stopped being theoretical.

It's worth noting that 2025 coincided with a clear increase in energy awareness on the part of regulators and international institutions as well. Reports on energy efficiency increasingly pointed out that losses in transmission and distribution infrastructure are not a marginal problem, but one of the real areas for optimization.

In practice, this meant one thing. The transformer stopped being a one-time cost. It became an element that generates a constant stream of costs or savings. Depending on how it was chosen. And how it really operates.

This also changed the way designers and investors talk to each other. More questions appeared about long-term scenarios. About load changes. About installation flexibility. About whether the solution chosen today won't become a burden in a few years.

Heading into 2026, it's increasingly difficult to ignore the topic of energy losses. Not because someone requires it. But because the numbers have started to speak for themselves.

And with such data, as we know, you can't win with narrative alone.

What the IEA's "Energy Efficiency 2025" Report Really Says and Why It Matters for Transformers

The International Energy Agency's Energy Efficiency 2025 report clearly shows that energy efficiency has ceased to be an add-on to the energy transition. It has become its foundation. Significantly, the IEA is not talking about futuristic technologies here, but about devices already operating in power grids today.

According to the IEA, the pace of global energy efficiency improvement is still too slow to meet climate goals while maintaining the stability of energy systems. The agency points out that the global rate of efficiency improvement should be around 4 percent annually, while in recent years it has realistically hovered closer to 2 percent. This difference translates directly into greater energy losses, higher operational costs, and increased strain on infrastructure.

The report strongly emphasizes the topic of power infrastructure. The IEA stresses that reducing losses in energy transmission and distribution is one of the quickest and most cost-effective ways to improve the efficiency of entire energy systems. It does not require a technological revolution, but the consistent application of proven, more efficient solutions in equipment like transformers.

Particular attention is paid to no-load losses and load losses in devices operating continuously. The IEA indicates that even small differences in the efficiency of individual infrastructure elements, on a systemic and multi-year scale, translate into very tangible economic effects. This refers to savings counted not in percentages, but in real energy costs and reduced demand for its generation.

The report also notes the changing nature of loads in grids. The growing share of renewable sources, energy storage systems, electric vehicles, and the electrification of heating is causing greater variability in energy flows. In such an environment, devices with lower losses and better partial-load efficiency gain importance, as they operate efficiently not only at nominal points but also under loads far from maximum.

The IEA also emphasizes the cost aspect. Investments in energy efficiency are among the fastest-returning actions in the energy sector. Reducing losses in power equipment decreases the demand for primary energy, lowers operational costs, and reduces pressure to expand generation capacity. This is particularly important under the conditions of unstable energy prices that the market has faced in recent years.

In practical terms, the IEA report sends a very clear signal: the efficiency of infrastructure equipment is no longer an image-related or regulatory choice, but a systemic decision. How transformers are designed and selected directly impacts not only the balance of a single installation but the resilience and costs of entire power grids.

For the industry, this means one thing. In the coming years, it will be increasingly difficult to justify choosing solutions with higher losses based solely on a lower purchase price.

Energy Efficiency as Industry's Key Response to Rising Energy Costs | Source: International Energy Agency, Industrial Competitiveness Survey 2025.

An infographic based on a 2025 International Energy Agency survey shows how industrial enterprises are responding to rising energy costs and price volatility. The survey results from 1,000 respondents across 14 countries clearly indicate that energy efficiency is today the most important strategic priority, surpassing on-site renewable energy investments, passing costs to customers, or reducing production.

The second part confirms that energy efficiency actions genuinely increase companies' resilience to energy price fluctuations. Over 80% of respondents rate their impact as critical, strong, or moderate, with only 7% noticing no effect. This data shows that modernizing power infrastructure, reducing losses, and better energy management directly translate into the stability of operational costs and the continuity of plant operations.

The conclusions from the IEA study clearly indicate that in 2025, energy efficiency ceased to be an environmental add-on and became one of the key tools for building industrial competitiveness and resilience to energy crises.

Dimensions, Logistics, and Installation. Seemingly minor details that caused major pain

If anything consistently derailed schedules in 2025, it wasn't spectacular failures. It was the details. Dimensions. Weight. Site accessibility. The sequence of work. Things that seem obvious at the design stage but in the real world can dominate the entire process.

For a long time, a transformer was treated as an element that would "somehow fit in." In practice, 2025 showed this assumption is becoming less and less valid. Especially when talking about prefabricated transformer substations, modernizations of existing facilities, or projects in densely built-up areas.

The first flashpoint turned out to be dimensions.

Differences of a few centimeters in width or height, which don't raise eyebrows in a catalog, on a construction site could mean having to change the entire foundation concept. In 2025, many projects painfully felt that a substation designed for a "standard transformer" is not always compatible with the actual device available at a given time.

The second problem was weight.

Transporting a transformer stopped being a simple logistical operation.

Load-bearing limits of local roads, access to the construction site, the availability of a crane with specific parameters. All of this started to matter earlier than ever. Projects that didn't consider these aspects during the planning stage often had to make up for it frantically at the end.

In 2025, situations increasingly arose where the transformer was ready, but there was no physical possibility to install it safely according to the original schedule. Additional days of downtime. Additional costs. Additional negotiations. And the question that came too late: did it really have to be this way?

The third aspect is servicing and accessibility after commissioning.

More and more people started thinking not only about how to install the transformer, but how to access it in five or ten years.

In 2025, there were more questions about service space, the possibility of safely removing components, and access to inspection points. This isn't a topic that impresses in a sales presentation. But it's a topic that comes back very consistently in operation.

An interesting phenomenon was that in 2025, more and more logistical problems began to be seen as systemic, not accidental.

International reports on infrastructure project implementation clearly show that underestimating logistics and the integration of technical elements is one of the main causes of delays and cost overruns. In a McKinsey report on productivity in infrastructure construction, it was pointed out that a lack of coordination between design and actual installation capabilities is one of the most frequent sources of time and money losses in energy investments.

In the practice of 2025, this meant a change in approach.

Designers began asking more frequently about things previously taken for granted. Contractors began incorporating logistics into the planning process earlier. Investors began to understand that compactness and predictable installation are not a luxury, but a real saving.

Dimensions stopped being a secondary parameter. They became one of the selection criteria.

Not because someone suddenly started liking smaller devices.

But because in 2025, the market saw very clearly what a mismatch costs.

Heading into 2026, it is increasingly difficult to think of a transformer in isolation from the place where it is supposed to work. Physical reality has returned to design conversations.

And it's likely here to stay.

Documentation, repeatability, and peace of mind during acceptance

If there was one thing that could halt a technically ready investment in 2025, it wasn't a lack of power or equipment failure. It was documentation. Or more precisely, its absence, ambiguity, or a disconnect between what was written and what was actually on site.

For years, documents were treated as a formality to be checked off.

Something that "has to be there" but doesn't necessarily require particular attention. In 2025, this way of thinking stopped working. Distribution System Operators (DSOs), inspectors, and investors began looking at paperwork not as an add-on, but as proof of the entire project's coherence.

The most common problem wasn't the complete absence of documents. They existed. But they were inconsistent. Declarations that didn't fully match the actual execution. Technical data sheets current "at the moment of order" but not necessarily at the moment of acceptance. Operation manuals that resembled a generic product description more than real support for the user.

In 2025, questions that were rarely asked before began to appear more frequently.

Does this transformer actually meet the specific requirements of the grid operator?

Do the parameters stated in the documentation match what was delivered?

Did the manufacturer anticipate operating scenarios that are now the norm, not the exception?

Repeatability proved to be a particularly sensitive point. Serial projects implemented in different locations began to painfully feel the differences between successive deliveries. The same transformer model, but with minor changes in execution. Different component placement. Different documentation. For operation, this isn't a detail. It's a source of unnecessary questions, risk, and stress.

Many contractors admitted openly that in 2025, the greatest relief during acceptance procedures was simply when the documentation matched up. Without excuses. Without "it's similar." Without handwritten additions. Consistency between the design, execution, and paperwork began to be treated as a technical value, not an administrative one.

Operational documents also began to carry increasing weight.

Manuals that actually help the user understand how the transformer works, when to react, and what to watch for. In a world where technical staff are increasingly stretched thin, the clarity and readability of documentation ceased to be a luxury. They became a safety element.

This trend is not accidental.

According to reports from international institutions dealing with technical infrastructure safety, one of the main sources of operational problems is communication errors and a lack of unambiguous technical information. Studies on the reliability of critical infrastructure explicitly state that standardizing documentation and procedures significantly reduces the risk of downtime and unplanned interventions.

In the practice of 2025, this meant a shift in emphasis.

Solutions were increasingly chosen that may not have been the most impressive, but were predictable. Ones that wouldn't cause surprises at the next acceptance. Ones that could be easily compared, serviced, and integrated into existing procedures.

Documentation stopped being an add-on. It became part of the infrastructure. And the peace of mind during acceptance that results from it turned out to be one of the most underrated benefits of a well-chosen transformer.

What to Choose After All This for 2026, and Why Peace of Mind Became the New Currency

After a year like 2025, the temptation to ask directly is natural. If so many things went off track, if theory was verified by practice, if details turned out to be decisive, then what transformer should be chosen for 2026.

And here it's worth slowing down for a moment.

Because the biggest takeaway from the last twelve months is not that the market needs something new. The biggest takeaway is that the market needs something predictable. Solutions that don't cause unpleasant surprises. That fit not only in the documentation but also in the substation, the schedule, and the budget. That comply with regulations not at the edge of tolerance, but with a real safety margin.

In this sense, choosing a transformer for 2026 is less and less a choice of the "technically best" option. Increasingly, it is a choice of the most sensible option in the context of the entire system. Energy losses. Load profile. Logistics. Documentation. Acceptance procedures. Operation in 5, 10, 20... years. This is why the conclusions from 2025 naturally lead to solutions like the MarkoEco and Teo Eco Tier 2 lines in the Energeks offering.

Not because they are the most impressive.

Not because "you have to."

But because they respond precisely to the problems this year exposed.

Meeting Ecodesign Tier 2 requirements without interpretive gray areas.

Low no-load losses where the transformer operates most of the time away from its nominal load.

Predictable dimensions and construction compliant with Distribution System Operator requirements.

Documentation that doesn't require explanations during acceptance.

This isn't a story about a single product. This is a story about an approach. About the fact that after 2025, fewer and fewer people want to improvise. More and more want to know that the decision made today won't come back in two years in the form of a problem.

This entire analysis, from the first section to the last, stems from a very simple assumption: listen and respond to the actual needs of the market.

In the end, we want to say one thing. Thank you.

For the conversations on investment sites.

For the tough questions in projects.

For the exchange of observations and knowledge.

For the feedback that sometimes stings but always teaches.

And for the fact that we increasingly think about the energy sector not only in terms of power, but in terms of responsibility and long-term consequences.

A new year in the energy industry is rarely calm. And that's good.

We wish you for 2026 not an absence of challenges, because they drive progress…

but more predictability where it matters. Less firefighting. More decisions that stand the test of time.

If these topics are close to you, we invite you to our community on LinkedIn.

We share market experiences, implementation insights, and conversations that usually don't fit in product brochures, for people who want to see further than the next acceptance procedure.

2026 is coming fast. It's good to enter it with energy that works for you!

Sources:

Cover Photo: Juan Soler Campello/pexels

International Energy Agency (IEA) - Energy Efficiency 2025

McKinsey Global Institute - Reinventing construction through a productivity revolution

When you stand next to a transformer substation and hear its soft hum, it's hard to believe that within that metal box, the lifeblood of the power network pulses.

And yet, most of us carry within us the same curiosity from childhood: the very same curiosity that made us wonder what was inside a golf ball, a ping-pong ball, or a tennis ball.

Who among us hasn't tried to drill, cut, or pry one open just to see what the "inside of the world" looks like? Let him who has not cast the first fuse ;-)

The transformer operates on this exact same archetypal impulse: the desire to peek where we don't usually look.

Inside a transformer, something fascinating happens. Current transforms as if in an alchemical process, and its heart is cooled by oil of near-laboratory-grade parameters.

What exactly lies beneath the steel cover?

And why does this structure work continuously for decades, despite extreme temperatures, vibrations, and voltages reaching thousands of volts?

At Energeks, we work with medium-voltage transformers every day – from design and testing to field implementations. We know that understanding the inside of a transformer is not just a matter of curiosity, but also of safety, efficiency, and compliance with standards.

This article is for contractors, investors, designers, and technology enthusiasts who want to look inside without the risk of electric shock.

After reading, you will know:

What key components make up an oil transformer.

What role the oil plays and how it works with the magnetic system.

How the construction of a sealed transformer differs from one with a conservator.

Which design flaws most commonly shorten its lifespan.

At the end, a bonus awaits you: a list of 5 operational errors that can destroy even the best-designed transformer.

Reading time: approx. 7 minutes

The magnetic core – the iron heart of the transformer

When you look at an oil transformer from the outside, you see a solid steel box, often enclosed in the concrete housing of a prefabricated substation. But the true life of this device pulses inside – where its iron heart beats: the magnetic core. Without it, a transformer would be like a body without a circulatory system – it would have no way to transfer energy from the primary to the secondary windings.

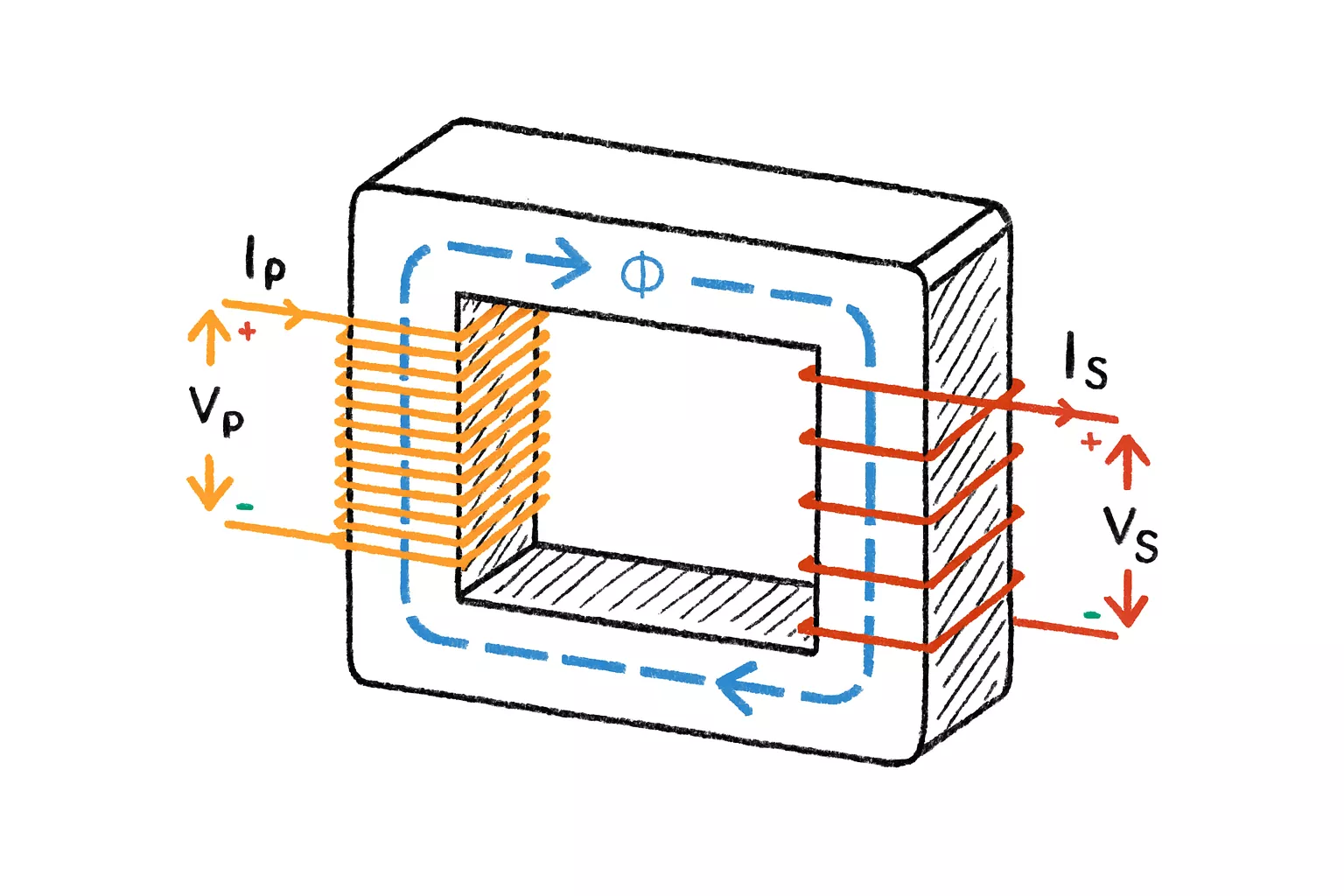

To understand how this works, we need to briefly revisit basic physics. A transformer doesn't "transmit" current directly between its windings. Instead, it uses the phenomenon of electromagnetic induction. When alternating current flows through the primary winding, it generates a varying magnetic field, which in turn induces voltage in the secondary winding. And all of this happens thanks to the core – the element that guides and concentrates this magnetic flux, like a well-laid highway for the electromagnetic field.

What is a transformer core made of?

Not from "iron," as is commonly said, but from electrical steel laminations – thin, precisely rolled sheets of silicon steel with low magnetic losses.

This is a very special material. Each lamination is coated with insulation to minimize the phenomenon of eddy currents, which could turn the transformer into an unwanted heater.

The thickness of a single lamination is usually 0.23–0.30 mm – about the same as a sheet of technical drawing paper.

The laminations are stacked in layers, like the pages of a book on energy, and clamped into packages.

This is called a laminated core. The thinner the laminations and the higher their quality, the lower the no-load losses – the energy the transformer consumes just to be "on," even without any load.

Two main types of cores are used in oil transformers:

Core-type, where the windings are wound around the vertical limbs of the core.

Shell-type, less common in medium-voltage power systems, where the windings surround the core.

Core-type designs have the advantage of being more compact and dissipating heat better – ideal for use with cooling oil.

What does core assembly look like in practice?

This is where theory ends, and true craftsmanship begins. A transformer core cannot have gaps or air spaces because every such micro-gap is a potential source of losses and noise. Therefore, the laminations are stacked with surgical precision. In large production plants, robots and presses are used for automatic stacking, but in smaller MV transformers, you can still literally see the human hand at work.

The laminations are overlapped in a "step-lap" configuration, which limits losses at the joints and reduces the characteristic hum. That hum you hear when standing by a substation is precisely the micro-vibrations of the laminations under the influence of the alternating magnetic field. For some, it's the sound of a stable, reliable grid; for others – a signal that "the transformer is working as it should."

What is the significance of grain orientation?

This is a term that sounds like it's from a metallurgy course, but it has enormous significance for a transformer's efficiency.

Silicon steel can be either non-oriented or grain-oriented (GO).

The latter has a crystalline structure oriented in one direction, allowing it to conduct magnetic flux more easily.

The result? Lower losses and quieter operation.

A transformer with a grain-oriented lamination core can have no-load losses 30–40% lower compared to older designs.

In practice, this translates to tens of megawatt-hours of saved energy over the entire life of the equipment.

What you see here is the moment when the oil-filled giant stands almost stripped to the bones, showing off its copper muscles without a hint of shame: the copper windings gleam like lacquered alloy rims, the insulation is layered like a perfect haircut from a master barber, and the core serves as the solid backbone of the entire structure. Here, you can see the precision, the craftsmanship, and the obsession with quality that defines this work.

Oil meets iron – how the core cooperates with cooling

The core is fully immersed in transformer oil, which serves a dual function: insulating and cooling. Heat generated by magnetic losses and eddy currents is absorbed by the oil and transferred to the tank walls, where it is dissipated. Modern transformers use forced oil circulation systems, allowing for higher unit power without overheating the core.

Why does all of this matter?

Because the core is not just a metal skeleton – it is the starting point for the transformer's entire efficiency. Its quality determines:

The level of no-load losses (i.e., the cost of energy the network "consumes" without any load).

Noise and vibration levels.

Operating temperature and the durability of the insulation.

And consequently – the transformer's lifespan.

As assembly floor engineers like to say:

"A bad core will eat up the best oil, the best windings, and the best design."

This is why, before a transformer reaches the substation, its core undergoes tests for inductance, losses, and magnetic permeability.

These are the tests that determine whether the iron heart will beat with a steady rhythm for decades to come.

Windings that transform voltage into usable energy

In the world of transformers, windings are like a bodybuilder's muscles.

They don't shine as much as a lacquered enclosure, nor do they buzz as distinctly as the core, but they do the heaviest lifting. They transform voltage, stabilize energy flow, and do it with a precision that begs for a comparison to martial arts masters: minimum movement, maximum effect.

An oil transformer has two main types of windings.

Primary, which receives high voltage like a gatekeeper at a power plant, and secondary, which outputs current in a form digestible for the network.

Copper – or aluminium – forms neatly layered, multiple turns that somewhat resemble a perfectly layered mille-feuille pastry.

Every layer has its insulation. Every turn must be in its place. Every millimeter matters, because we're talking about electric fields capable of generating voltages that can, in a second, turn a simple assembly error into a fire, an oil blockage, or a flashover nobody wants to witness.

The windings in an oil transformer are also the element that most reveals the manufacturer's character.

A single glance at the geometry, cooling layout, and the way the leads are brought out is enough for an experienced engineer to assess whether they are dealing with top-tier craftsmanship or a budget experiment that probably shouldn't get anywhere near an MV switchgear room.

The winding line tells the truth. It's either clean, uniform, and perfectly wound, or it screams that something was rushed.

It's worth remembering that windings operate at temperatures that can exceed one hundred degrees Celsius. Oil cools, but you can't cheat physics.

This is why insulation materials are so crucial – typically oil-impregnated electrical paper, which acts as both a blanket and a barrier.

The better the impregnation and the more uniform the layers, the longer the transformer will work without complaint. Leaving micro-gaps, overheated copper, or using the wrong insulation class – all these shorten a transformer's life like sleepless nights shorten a human's.

This is precisely where all the magic of voltage conversion happens.

A varying magnetic field arises in the core, which induces voltage in the secondary winding. It's like a dialogue you can't hear, but you see the results – in the form of usable energy that reaches homes, pumps, factories, energy storage systems, and all the other infrastructure we take for granted.

Well-designed windings also guarantee stability during short-circuits and overloads. A transformer that is "copper-resistant" will withstand more, because its windings won't collapse, shift, or break in critical moments.

The difference between a robust and a weak transformer often only reveals itself after the first short-circuit – and then there's no more debate about which copper was "the right one."

Finally, it's worth noting that windings have their subtle charm. There is a certain geometric aesthetic, order, and rhythm to them. A transformer with such windings will reward you with years of quiet operation. It's one of those relationships where precision truly matters.

If you want to see how these windings are created step by step, check out our article:

How a transformer is made: 10 stages of oil transformer production

It's a great complement to this part of the post, as it shows the entire process from the first lamination, through winding the copper, to final testing and assembly. It perfectly rounds out the topic.

Insulating oil, the invisible guardian of temperature

If a transformer were a living organism, the insulating oil would be its lifeblood.

A quiet, hardworking substance that doesn't demand attention, doesn't shine, doesn't smell spectacular, but performs a task so vital that without it the entire system would collapse like a house of cards.

This insulating oil stands on the boundary between smooth operation and the kind of catastrophe operators prefer to see only in training scenarios.

Transformer oil serves two main roles.

First, it insulates, pushing voltages apart as effectively as if it stretched an invisible protective net between conductors.

Second, it cools—and it cools literally every element that generates heat.

Copper (or aluminium) and the core have a tendency to heat up their surroundings. The oil absorbs this heat, transports it to the tank walls, and dissipates it to the environment. Without it, the transformer would be like a convection oven, only decidedly less pleasant.

Two main categories of oil dominate the market.

The first is mineral oils, the classic of the power industry. Stable, predictable, cost-effective, with well-researched characteristics.

The second is ester oils. They are increasingly chosen by designers of substations and photovoltaic farms because they are biodegradable and have a higher fire point. In practice, this means an additional safety margin.

For many investors, it also matters that ester oils penetrate the insulating paper better, slowing down its aging.

The operating temperature of a transformer is a complex puzzle.

Every degree increase translates to faster aging of the cellulose insulation. And it's the insulation, not the copper, that determines the longevity of the entire device. Therefore, good oil isn't a fancy extra. It's an investment in decades of stable operation.

Excessive moisture in the oil, contaminants, or chemical degradation can lead to what in the power industry is described succinctly and directly: trouble.

An interesting fact is that transformer oil keeps its own chronicle of the device's life over the years.

Every chemical micro-flaw leaves a trace in it.

This is why DGA testing, or Dissolved Gas Analysis, is like reading a flight recorder.